Interview Questions For Patricia Briggs

Most beginning authors crave interviews, and the majority of seasoned authors dread them. This is only partially due to authors being anti-social introverts prone to bouts of crankiness. It's also because so many interviewers ask the same questions. How many times can you write two paragraphs on "Why did you become an author?" before it becomes onerous?

Professional interviewers generally take the time to read at least some of the author's work, read previously-published reviews, and study their subject's biography. They are skilled at formulating interesting questions tailored to their subject and their body of work. A well-crafted interview can be a fascinating voyage of self-discovery, and the guttering flame of enthusiasm can be rekindled by thoughtful, relevant questions.

However, not all interviewers are professionals who can afford to spend days in preparation. There are overworked convention volunteers who just need some basic facts for the program book, and bookstore staff looking for additional information. Then there are the teeming masses of high school or college students who have been given the dreaded Iinterview a Working Professional assignment. This page is intended to assist those of you who need answers to common interview questions, and help save Patty's sanity.

If you happen to be one of these unfortunate students, let me first refer you to a wonderful article written by Lauren Panapinto. It has some helpful tips for you, and a little information for your teacher. The Dreaded Flood of Student Interviews. You should definitely take time to read it.

What Patty Should Have Said

By: Mike Briggs

Patty spent hours coming up with detailed, accurate answers to these interview questions. If you're actually interested in accuracy they're perfect, but they're about as interesting as cold oatmeal. The sad fact is that an author's life isn't all glamor and glitter, and truth may occasionally be stranger than fiction, but it's usually a lot less interesting.

I decided to shamelessly impersonate Patty and provide the answers she should have given if she weren't such a goody-two-shoes. Patty has also approved these answers, so you can use them for your school reports, web pages, or whatever you need. It's all nice and official.

- Why did you decide to become an author?

-

When I was young I wanted to be a horse. Since I couldn't be a horse, I read books about horses. My sister eventually persuaded me to read something other than horse stories, and introduced me to Andre Norton. Of course, I was soon reading everything I could get my hands on.

However, in my mind, authors were like rock-stars. It never occured to me that it was something a regular person could choose to do. Then, when I went to college I discovered that my roommate was a writer. She had dozens of spiral-bound notebooks filled with hand-written stories. She proved that an normal person could choose to write a story. That realization was, eventually, life-changing.

When my husband took a job in Chicago I was frequently left alone with a hyperactive toddler in a tiny apartment. When he finally took a nap, I needed something to occupy my time (besides housekeeping, of course. Housekeeping has never been on my top-ten list). I chose to spend the time writing down a story, which gradually grew until became a book.

When the story was finished, I was tempted to simply slide it into a drawer and forget about it. My husband urged me send it to some publishers. That story,Masques, became my first published novel.

-

I was a child in the 70's, when society's mantras were "Be what you want to be." and "Follow your dreams wherever they lead you." Perhaps they should have advocated something more practical, because I ended up with degrees in History and German. History because I loved it, German because I'm too stubborn to give up on something I'm not good at. I was virtually unemployable.

I thought I could get a teaching job, but quickly learned that history teacher is a position reserved for football coaches, while German teachers are generally part time and expected to actually speak German. My employment prospects were bleak, but my student loans were abundant.

I considered being a movie star. The work doesn't look too hard, and the pay is good, at least for the top-tier folks, and why would I set my sights any lower? But, the thought of doing kissing scenes ultimately dissuaded me.

I was getting desperate. Doctor? Too much icky stuff. Lawyer? I don't look good in lawyer-wear, they might even have to wear nylons. Politician? *shudder*, no thanks, I'm still using my soul. I was pretty much down to burger flipper or meter maid when it happened . . .

I watched Romancing the Stone. The main character is an author. In the movie, she was doing pretty well for herself. She ended up getting romanced by Michael Douglass, which didn't sound too bad. Authors get to set their own hours, be their own boss, work in their pajamas and have fabulous adventures. Suddenly, my choice was easy!

- Where do you get your story ideas?

-

Stories imitate life, and there's no substitute for having a little mileage on the odometer when plotting stories. I've also yet to find a fast, easy and reliable method to produce a great (or even workable) story idea.

For me, it's a messy and sometimes lengthy process. I start with a very vague, nebulous idea of the type of story I want to tell. For example: "traditional medieval fantasy". Of course there will be castles and sword fights, and deeds of bravery, but that's a long way from a story.

With the foggy idea in place, I start trying out various details. Some details take shape earlier than others. For me, it's usually the characters who first coalesce into something a bit more firm. It's important to note that, at this stage, nothing is set in stone. I may imagine a character, give him or her some shape and dimension and the beginnings of personality, and decide that I don't like the way this character changes my imaginary world. For example, maybe I was imagining a cocky, swashbuckling Errol Flynn sort of character, with doublet and rapier, but I've been imagining a setting more like twelfth century England. They obviously don't go together, so I have to decide whether to change the setting or the character. It can be a long process, and there's a lot of mental tweaking and adjusting.

Eventually, I'll arrive with the basis of a story: a character in a place with a problem. My efforts are focused on insuring that the character is charismatic, that he fits in that place, and that his problem is sufficiently interesting to carry a novel. When those three elements are finally right, it's time to pick up the keyboard and begin actually telling the story.

I don't plot (much) in advance. I'm a seat-of-the-pants writer (also called a pantzer) so the rest of the ideas come to me gradually as I write the story.

-

The stock answer, of course comes from Harlan Ellison. "Take $2, put them in a stamped, self-addressed envelope and send it to Schenectady, and they’ll send you back an idea." Sadly, Harlan never gave the address of his little shop.

I'm going to recommend one of two methods:

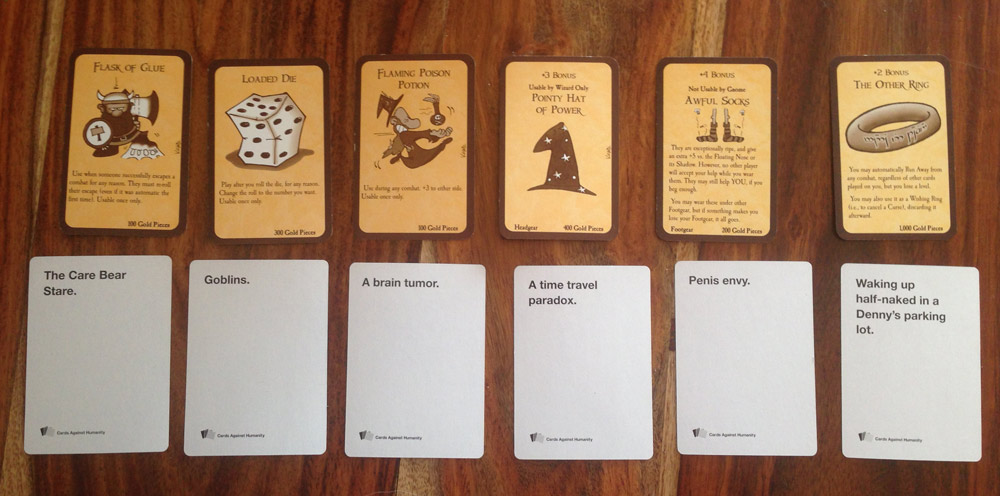

The first method will require a few dollars and a visit to your local gaming store. You need to by two separate card games:Cards Against Humanity and Munchkin. Please note there there are several varieties of Munchkin available, choose the one that best matches your preferred story style. Now go home and draw the shades so the neighbors can't see.

First, open your Munchkin game, shuffle the deck, mutter whatever mumbo-jumbo makes you feel mystically empowered, and deal six treasure cards. Then open Cards Against Humanity and deal six of the white cards. You may discard one item from either set, and randomly select a replacement (Who am I kidding? You can rifle through the deck and pick a good one!). Now look at your cards, you should have something like this:

These are the building blocks of your story. All you have to do is figure out how to tie these elements together and you've got your story. Look at the cards above: Time travel paradox, The Other Ring, Goblins, A Flask Of Glue, Penis Envy, etc. Can't you just feel your muse whispering ideas to you?

The second method is a time-honored author tradition: steal. Find somebody who did something awesome and make it your own. File off the serial numbers, change some names to protect the insolent, and claim you invented it. Hey, virtually the entire fantasy genre is based in ripping off Tolkien. The trick is to get really good at filing off serial numbers. You might also consider stealing from multiple sources, and then mixing up the parts. This is considered advanced larceny, but it's harder to trace and easier to

fencesell. - Do you write full time, or do you have a day job?

-

I currently write full time, but it's not quite as simple as that.

For many years I had a day job. All sorts of day jobs, in fact. I've worked as a convenience-store clerk, insurance-office gopher, substitute teacher, museum assistant and a half-dozen more. Some of these jobs were full time, and some were part time. I usually worked during the day, and then wrote at night after everyone was asleep.

Our finances gradually improved, and writing time grew to fill the available hours. Finally the day came when I was able to quit my day job and dedicate my time entirely to writing. I can remember doing some simple calculations along the lines of, "If I'm currently working three hours a day, and writing one book a year, then I should easily be able to do two books a year, probably three!" Multiplying the earnings of my current books by three painted a nice enough financial picture to quit my day job.

I soon discovered that, while I had far more hours, my creativity hadn't magically multiplied. I have maybe four hours a day of good creative output, and then it's time to do something else. Fortunately, there's always more to do. There's editing, marketing, and social media. There's foreign editions, research and networking. And, just in case I'm bored, there's always something to do on the horse farm!

Because I only have a certain amount of creativity, my writing tends to follow a predictable pattern. In the early phases of writing I spend a great deal of time just exploring all of the possible story threads by following multi-branched decision trees. If the characters do this, that will happen, then they will do this, then they all die. Back up and try again. I'm not plotting all the way to the end of the book, usually just the next couple of chapters. However, beginnings are full of infinite possibilities, and I'm still trying to decide which paths to follow and what "shape" this story will take.

This early phase has a lot of creative, mental work, which probably looks like daydreaming to anyone on the outside. In fact, that woozy half-awake state in early morning is perfect for this sort of work. However, the pages come very slowly, and after a few hours my brain is tired.

As the book progresses, the number of potential plots gradually diminishes, which means there's less thinking and more writing. Pages come progressively more rapidly, and I can work longer hours on writing. By the end of the book, I'm usually pushing a deadline, but with the plot firmly decided I can work fourteen or sixteen hour days, occasionally writing twenty or thirty pages in a day.

Even writing full time, it's not a steady 8-hours Monday through Friday sort of job. It just doesn't work that way.

-

You serious? Look,I'm not saying, exactly, that there's a code of silence among authors. I'm just saying that, hypothetically speaking, there might be writer's guilds and organizations that don't like scabs, and certain, shall we say controversial aspects of the profession are best glossed over. You ever seen an author with ten broken fingers? Let me tell you, it cuts into productivity something awful.

So, you're not gonna' hear many authors blabbing about how many hours they actually work, capiche? The reason, ya' see, is that authors do a whole heck of a lot of day-dreaming, wool-gathering and navel-gazing and we call it work. The authors guilds negotiated a —whatcha' callit?—special dispensation and it's all copacetic. We get to put in about half the actual work of anybody else, and the rest of the time we're supposed to hang out in coffee shops wearing, you know, jackets with leather patches on the elbows and stuff. It's a good gig, but can you imagine the stink if the teamsters or dock workers knew about this? Saints preserve us!

Ya know what? I talk too much. Freakin' occupational hazard, that what it is. Enough already. Yeah, I work full time. Overtime even. Weekends and holidays too. Anybody says different is lyin'. And now, I gotta get back to it, my shift started two minutes ago.

- Why do you write genre fiction, specifically urban fantasy?

-

In a purely rational world, I suppose one would look at the publishing landscape and decide what to write based on market expectations. I'm sure there's a spreadsheet somewhere that calculates mean earning by genre, and cross-references the likelihood of earning prestigious awards with literary theme. It might well show that stories featuring critically-ill young women dying with dignity have a high-probability of garnering critical acclaim and that dystopian-world romances are most likely to earn financial rewards.

However, at least for me, it takes anywhere from six months to a year to produce a decent book. A year of my life, in which my most productive time is spent thinking about that story. I don't want to put that kind of effort into a story I'm not interested in, and I'm convinced that if I tried to "hold my nose" and write something I didn't care about, it would show in the finished product.

It's been said that most authors write the book they wanted to read, but couldn't find. I honestly like fantasy, including urban fantasy. It's a flexible genre. I can tell a swashbuckling adventure story, a steamy romance, or a hard-boiled detective story. If I wrap it with a sprinkling of magic and a dash of the fantastic, I'm good. What other genre offers such flexibility?

I write what I love because life is too short to waste on things you aren't passionate about.

-

Well, to write literature you have to be literate. I do read some literary fiction, you know that stilted, pretentious, self-aware stuff that literature professors write for other literature professors. It's like watching a lone ice skater carving impeccable figures on the flawless ice of a pristine lake on the perfect winter day. In short, boring.

Science Fiction is really interesting, but they take the concept of world-building literally. A quick glance at a copy of Numerical Methods in Astrophysics: An Introduction by Bodenheimer et. al convinced me that I wasn't ready to tackle building my own universe just yet. My symplectic integrator is barely up to Keplerian ellipses, and Lyapunov time estimation still seems counter-intuitive.

Since I have a degree which included lots of medieval European history, I did straight fantasy, but even there the world building is terribly complicated. Every little village needs transportation and industry, imports, exports, politics and governance. There's a million little decisions — are their arms and armor 15th century or 17th? What level of metallurgy is available, and who controls the technology? I played that game for a while, but then I found something even easier . . .

Urban Fantasy. There was a gameshow years ago with the motto, "Where the rules are made up and the points don't matter!" Urban Fantasy is exactly that. It's based on the real world, so I don't have to invent anything. If my characters want a slushie they head to a 7-11 like anyone else, and I don't have to explain the economy and technological underpinnings that make a slushie machine possible (though I'm pretty sure there's magic involved.)

Of course, when I don't like the real world, I can just make something up. Werewolves, vampires, witches and trolls, what an awesome playground to tell stories in. This is a fun place to play, and I don't need any differential equations!

- Authors are traditionally cast as reclusive loners. Are you?

-

Writing is a career that will test the social mettle of just about anyone. On one hand, an author needs to be supremely comfortable with their own company. Writing a novel requires many hours (for me, probably a thousand or more) of sitting alone staring at a computer screen, listening to the voices in your head. That's enough to drive some people crazy.

Conversely, promotion requires the author to fly around the country attending conventions and signings. You'll meet thousands of people, shake hands, take selfies, tell jokes and just hang out. You may also be writing numerous emails, blog posts, podcasts or whatever. This is a job for a dedicated socialite; a professional schmoozer.

Somehow, an author has to be both a dedicated introvert and a flamboyant socialite. I'm very shy by nature, but over the years I've learned to adapt pretty well to socially-demanding situations. I enjoy meeting people and chatting with them. I'm genuinely interested in other people. And, at the end of a half-day of being intensely social, I am more than happy to go lock the door on my hotel room and decompress for a few hours. I'm neither as shy as I used to be, nor outgoing enough to be truly comfortable with big signings and conventions. This career has changed me, and I've got a foot in both worlds.

-

I refuse to be categorized, and reject your binary world-view. I am complex, and ever-changing. Plato once asked "What is that which becomes but never is?" That's me. I'm always becoming something, which means there's shades of gray, intermediate steps that disprove your false black-and-white dichotomy . . .

That's it. That's all the bargain-bin philosophy I've got. Sounded good for a second though, didn't it?

I'm mostly a loner, but I have gotten better at doing conventions without having anxiety attacks. I'm always glad, though, to get back to my quiet little horse farm.

- Does your writing require research?

-

Good writing always requires research. In writing, the author's job is to create a convincing illusion of a complete, believable world. You can't build a believable world with foggy references and vague arm waving, you're going to need details. They say the devil is in the details, and it certainly seems that way.

If your medieval hero pulls on a linen shirt, you have some questions to answer. Does your hero live in a land where flax would grow? It's a moderately finicky plant, so that puts some real limits on the local ecology and climate. If not, who are they trading with? Where are the facilities for processing and weaving the fabric? It's not something done by the average housewife. That linen shirt just raised a dozen questions in the minds of every reader who knows their textiles, and their trust in you depends on getting the details right.

Guns are my personal nemesis. For some reason gun-related information slips out of my brain like it was teflon-coated. However, a very large percentage of urban fantasy readers are gun literate. If I have a character with a Desert Eagle (Hollywood's favorite hand-cannon) concealed under their little black cocktail dress, brows will furrow in consternation. Not all handguns have safeties, decockers, or external hammers, and magazine capacities matter. I try to be extra-careful, but a couple of errors have stilled slipped through.

There's a million little details in any world, and if you get them wrong the readers will notice. They'll gradually stop trusting you. If they can't trust you with guns or agriculture, why would they believe you when you talk about dragons or werewolves? A reader's trust is fragile, and research is how you earn it.

-

Great writing requires research, period. I aim for "pretty good", which greatly increases my free time. - What is your process? How do you write?

-

Once again, there's no magic involved. I think a lot of aspiring authors are convinced that there is some secret recipe of background music, scented candles and keyboard layout that will make writing easy. If there is such a recipe, please let me know!

With that said, it's easier to be creative when you're physically comfortable. Having a dedicated writing space, even if it's just a desk that's yours makes a tremendous difference. I keep my office a bit warmer than my house, because I'll be sitting still for hours. Background music, scented candles, whatever makes you relaxed is fine. Just remember you're setting up a work area not a seduction scene; scattering rose petals around the workplace might be taking it too far.

Once you're comfy, it's time to work. As I mentioned, I usually start a story with an idea for a character, a setting, and a problem. I refine these details as I write them, so I spend a lot of time thinking with a half-finished sentence on the screen. Each decision you make early on is going to shape the whole story, so think it through carefully. Then you just keep going to the end.

I've often compared it to weaving. As I work, I'm weaving setting, character, plot and a thousand little details into a tapestry. The part already woven determines which threads are loose, which elements are in-play, and whatever I'm writing has to mesh smoothly. Unlike an actual weaver, I can go back and selectively re-work elements of the tapestry to my liking. In fact, when good ideas strike late in the creative process, I often talk about going back to "weave" them into the story so things don't suddenly show up out of the blue in chapter ten.

I've detailed more of my thoughts and writing process in Building a Strong Story: 7 Critical Elements.

-

This is a terribly over-thought topic. There are a great many Coffee-Shop authors who spend their lives discussing the art and craft of writing, but seldom write anything. Talking about writing becomes a way to procrastinate the hard work of pulling a story out your head.

So here's the real answer. I write by putting my bum in a chair and staring at an unforgiving blank screen until I think of some words. Then I type them. Then I stare at the screen until I think of more words, and type them. At some point, I'll go back and erase some of the words I've typed, and try to replace them with better words. That's all there is to writing.

Still looking for inspiration? Check out this video from the Christmas classic Santa Claus is Coming To Town and just Put One Foot In Front Of the Other. So, are you the type of writer that needs an Ascot and a meerschaum pipe, or the type that needs a laptop and quiet place to work?

- Which authors influence your writing?

-

I'm a voracious reader, and I'm relatively genre-agnostic. I mention this because I think everything an author experiences influences their thoughts, which ultimately influences their writing. In that sense, there are hundreds or thousands of authors who have influenced my own writing. In my early works, I can often read a passage and tell you exactly what I was reading when I penned that passage, which is sort of embarrassing. Hopefully I've gotten better about writing in my own voice.

With that said, there are some authors who stand out:

- Andre Norton was my gateway drug and opened worlds of wonder and delight for me. She told huge stories with very few words.

- Anne McCaffrey who taught me to fly with dragons and the wonder of being a starship, instead of just piloting it.

- Dick Francis is famous for his horse-racing mysteries (which I love). But what I learned from him was how to write conversation that pushes the story forward.

- John Steinbeck who, like Andre Norton, used very simple sentences and words to tell stories that were anything but simplistic. I can't manage the power of his prose, but I use him to remind myself that complex is not necessarily more important.

- Lois McMaster Bujold makes heroes out of unusual people. She reminded me that heroes are the people who just get the job done as best they can.

-

As a young girl, I lived vicariously through books.

- Anna Sewell wrote Black Beauty, a book I read so often that it inadvertently shaped my world view. I was startled, reading it to my own children, that I could still quote large portions of the book from memory.

- Marguerite Henry wrote a number of books, including Misty of Chincoteague, which I devoured with a passion known only to the young.

- Walter Farley wrote The Black Stallion which was excellent, but sadly followed by a string of far lesser works, which I only read five or six times each in protest.

- Alois Podhajsky who wrote several training manuals, including the Complete Training of Horse and Rider. After all, the best-trained horses begin with a solid foundation.

Oh, I'm sorry. I didn't read the question. I thought you meant which books influenced me, personally. Have I mentioned I was terribly, obsessively horse-crazy in my youth? Apparently, there's no cure for that, and even living on a horse-farm surrounded by beautiful creatures is only a palliative measure.

- Are your characters based on real people?

-

In a general sense, part of being an author is looking at the people around you and asking, "Why do they do this? What motivates them?" That said, basing a character entirely on someone you know--or worse, on yourself--is usually a mistake.

If you've based a character on one of your friends or on yourself, you've set some artificial bounds on that character. There is truth to the saying that authors torture their characters: pain, betrayal and desperation are common in books. The person who can vicariously torture their friends, or themselves this way may need counseling. Also, characters need to have flaws, and it's always easy to see the flaws in our friends. If you write those into a story, you may lose a friend or two.

Of the (probably) thousands of characters I've written, four have been deliberately based on people I know. Zee, my fae mechanic, is loosely based on a dear friend, our own VW mechanic, who was dying from cancer as I began the first Mercy book. He was a wonderful human being, a real character, and I found that he was the perfect mentor for my little coyote. Buck died before the book was in print, but he was delighted to play his role. Friends, not understanding just intimate a good character portrait is, sometimes asked to be put into books. I usually resist, but I had a friend who was an antiquarian bookseller who told me that Mercy needed to do some research in the store he helped to run. A couple of books later, I discovered he was right. It was supposed to be a walk on part--so I didn't see the harm in it. Then a couple of books later, I thought the story was going to require me to kill him...er, his character. I called him and told him that I might have to kill him--and he was okay with it. Finally, early on in my career, I had two characters (in different books) very loosely based on one of my husband's co-workers. I just picked a couple of traits that time, not the whole person, but usually I don't know where I get the bits of character I shove in a paper bag and shake together. But using real people to make your characters is full of possible disasters. I don't recommend it.

-

Not usually. Unless someone irritates me. Then I find a way to work them into my novel and kill them horribly. I find it cathartic.

- What part of writing do you find most challenging?

-

It depends on the book. Sometimes I have a hard time getting a character's voice firmly in my head. If I don't know who they are, what they want, and what they feel like I can't write them convincingly. I struggle every book with Anna (from Alpha and Omega). She's very unlike me. She's so quiet and soft-spoken that it takes me a while before I remember she's got a core of spring-steel and rawhide and if she gives ground, it's only to gain a tactically-superior position.

Sometimes the middle doldrums seem insurmountable. Since I don't write from an outline, I'm sort of navigating by feel, and when things don't work I often have to backtrack, delete pages (or chapters) and explore a new route. I'm gradually getting better at finding my way through them. The problem is that when it's not going well, when I'm adrift without a sense of direction, it becomes far too easy to procrastinate, or find something else to do. Discipline is hard.

Occasionally, the sheer weight of world-building becomes crushing, especially on a long series. How many characters have walked on-stage in the Mercy-Verse? Literally dozens of them are important enough to have their own story arcs and timelines. For example, even though Tony the cop may only show up every two or three books, his life isn't frozen. I can't just polish up an imaginary Tony figurine and put it in a drawer for later. Somewhere, in the back of my mind, his character arc is playing out as well, so when he shows up again in a book or two he'll be a slightly different person, changed by the events that didn't make it into print. Do that for thirty or forty characters, while trying to keep track of everything you've said in previous books, and it can become exhausting. I haven't found a cure yet.

-

The part where I'm halfway done with the draft of a novel and the pirate sites are already offering the whole novel for free download.

That's just mind-boggling. Where did they get the finished version? If they can time-travel to when the book is finished, could I? It would certainly save a lot of work. Who decides who has access to time travel, and why do they let the pirates use it? If I skipped writing the book and just jumped to the time when it was done, would it really be done, and if so, who would have written it? It seems unfair that the pirates can jump forward to see the finished product, while I must plod along day-by-day writing until the end. To whom might I complain about this unfairness? These are sorts of challenges that keep me awake at night, pondering.

- Do you write the story, or do your characters take over?

-

I can actually shed some light on this one. It's something most beginning writers struggle with, and it can be disconcerting.

The human brain is a terrible computer in most respects. Our memories are unreliable, our perceptions are easily deceived, and even the best of us can't do math as well as a cheap calculator. We are, however, remarkably good at pattern recognition, and that turns out to be critical when dealing with characters.

I've talked a little bit about creating a character, and the amount of thought and craft that goes into that. You almost certainly know more about your protagonist than you do about most of your friends. Your mind is going to use that to play tricks on you. Here's how it happens:

There comes a point when your plan calls for a character to do something, but when you sit down to write the scene the character flaty refuses. You issue orders, and he gets grossly insubordinate. You know this character is a figment of your imagination. Now you can almost hear his impudent voice explaining that he's not going to follow your stupid outline, he's got plans of his own.

Before you check yourself into the nearest psychiatrist, think about what's happening. You invented a character, complete with goals, motivations and personality. Your brain is treating your character like a real person—that is what you wanted, right? Being able to predict how other people are going to react (especially when they're not acting rationally) has been a survival trait ever since the first hominids formed social groups. Your brain is really, really good at this sort of predictive analysis, and it's telling you that this particular person, in this particular situation, isn't acting right. Your brain isn't malfunctioning, it' simply trying to warn you. So there you sit, arguing with an imaginary person.

After the first few times this happens, you sort of get used to it. The character's motivation is wrong. Change the character or change the story until the character shrugs and says, "OK Boss, I'm on it!" and goes back to doing what you've asked him to do. Then take a moment to say, "Thank you, brain, for helping me make my character act rationally, my readers will greatly appreciate it."

-

It was touch-and-go in some of my early books, but I've developed a system that works. I'm the author, and that means the final decisions are always mine. However, I'll consider any suggestions the characters may want to put forward. I try to be fair and evenhanded, and the characters have occasionally had some very good suggestions. For example, there was the time that Oreg argued that he wasn't really dead. I told him that his death scene was already written, and I wasn't going to change it. He admitted that his death had been necessary, but maintained it was a bad ending. Ultimately, I had to agree with him.

One thing I won't stand for, however, is characters planning rebellion behind my back. There are, occasionally, traitorous characters scheming to overthrow me, but I simply won't let them take over. Unfortunately, I have to kill a couple of characters every now and then to remind the others who's in charge. What readers see as a tragic character death is, in point of fact, an execution. Sad, but necessary. I frequently remind my unruly subjects that they are supremely fortunate to inhabit my universe, and not that of a murderous tyrant like George R. R. Martin.

- When a reader closes one of your books, what do you hope they're left with?

-

Do you remember, in Greek mythology, the story of Pandora? Pandora was the first woman on Earth. She opened a jar from which flew all manner of evils: disease, pestilence and death entered the world, never to be eradicated. However, when poor Pandora examined the jar she discovered that it held one more thing: Hope.

Like most authors, I hope that my stories are entertaining. My writing sometimes goes to some dark places, and bad things happen. My worlds are not all fluffy bunnies and prancing unicorns. In the end, though, when the reader has turned the last page, I want the reader, like Pandora, to discover a bit of hope. The darkness cannot hold back the light forever. I would like them to leave my world feeling a little bit better than when they entered. That is the true magic of storytelling.

-

Mild insomnia, sufficient finances, and a raging desire to buy the next book!

- Do you have any advice for new authors?

-

Read. Read the great books, the classics, to understand the history and power of the craft. Read good books, and then ask yourself what made them good. Read bad books, and learn from them as well. Know your chosen genre well enough to navigate its tropes with confidence. Know other genres so that you can borrow from them, and enrich your writing. Read until the cadence of story and plot are part of you, and you will never fear to steer your story into deep waters, for the path is written in your heart! (OK, that was cheesy. We just watched Moana, and I couldn't resist. Sorry.)

Oh, and don't be afraid to make mistakes. This is an art, not a science. It's messy, and mistakes are part of the fun.

-

Sure. A fool and his money are soon parted. Also, take everything you read with a grain of salt, someone could be pulling your leg.